Play with R data sets in Python

Posted on Wed 27 January 2016 in misc • Leave a comment

R comes with a plethora of data sets to play with out of the box, which really come in handy when you're exploring how new functions work. While Python's pandas package tries to emulate the best parts of R's data frames, it can be tedious to find "real world" data sets to load or try to create your own toy data sets. Well, thanks to the rpy2 package (and some incredibly arcane code snippet that will likely change in the future) you can import any of R's data sets directly into a pandas data frame!

The rpy2 package itself is actually quite a gem. If you have R 3.0+ installed in your environment, rpy2 provides an interface to execute R code from python and interact with the results as if they were python objects. This makes rpy2 like a super-library that lets one use some of the best parts of R from python. I haven't dared try anything too complicated with rpy2 just yet, but I knew if I could just get R's data sets into a pandas data frame that I'd end up using them. Take a look at all the data sets at your fingertips in R: (https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-patched/library/datasets/html/00Index.html)

If you'd like to inspect the data sets from R itself:

# Start R interpreter from bash

$ R

# Interactively look at what data sets are available

> data()

# Data sets in package ‘datasets’:

#

# AirPassengers Monthly Airline Passenger Numbers 1949-1960

# BJsales Sales Data with Leading Indicator

# BJsales.lead (BJsales)

# Sales Data with Leading Indicator

# BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand

# ...

# volcano Topographic Information on Auckland's Maunga

# Whau Volcano

# warpbreaks The Number of Breaks in Yarn during Weaving

# women Average Heights and Weights for American Women

# Let's look at the BOD data

> BOD

# Time demand

# 1 1 8.3

# 2 2 10.3

# 3 3 19.0

# 4 4 16.0

# 5 5 15.6

# 6 7 19.8

# Use the R Help to to view the description, the source, and some examples

> ?BOD

# Summarize it from R

> summary(BOD)

# Time demand

# Min. :1.000 Min. : 8.30

# 1st Qu.:2.250 1st Qu.:11.62

# Median :3.500 Median :15.80

# Mean :3.667 Mean :14.83

# 3rd Qu.:4.750 3rd Qu.:18.25

# Max. :7.000 Max. :19.80

# Let's look at the AirPassengers data set, too

> AirPassengers

# Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

# 1949 112 118 132 129 121 135 148 148 136 119 104 118

# 1950 115 126 141 135 125 149 170 170 158 133 114 140

# 1951 145 150 178 163 172 178 199 199 184 162 146 166

# 1952 171 180 193 181 183 218 230 242 209 191 172 194

# 1953 196 196 236 235 229 243 264 272 237 211 180 201

# 1954 204 188 235 227 234 264 302 293 259 229 203 229

# 1955 242 233 267 269 270 315 364 347 312 274 237 278

# 1956 284 277 317 313 318 374 413 405 355 306 271 306

# 1957 315 301 356 348 355 422 465 467 404 347 305 336

# 1958 340 318 362 348 363 435 491 505 404 359 310 337

# 1959 360 342 406 396 420 472 548 559 463 407 362 405

# 1960 417 391 419 461 472 535 622 606 508 461 390 432

> quit()

Now let's get that data into Python. Note that here, I'm using pandas 0.17.x and I'm following the related documentation. As of 0.17.0 there appears to be a deprecated interface to rpy (predecessor to rpy2) in pandas that's much cleaner to use, but not future-proof. I will use the (ugly) supported version and expect that this will become cleaner in later versions of pandas.

## Arcane incantation

>>> from rpy2.robjects import pandas2ri

>>> pandas2ri.activate()

>>> from rpy2.robjects import r

# Now, provide your data set name to the r object

>>> df_BOD = pandas2ri.ri2py(r['BOD'])

>>> df_BOD

# Time demand

# 1 1 8.3

# 2 2 10.3

# 3 3 19.0

# 4 4 16.0

# 5 5 15.6

# 6 7 19.8

>>> df_BOD.info()

# <class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

# Int64Index: 6 entries, 1 to 6

# Data columns (total 2 columns):

# Time 6 non-null float64

# demand 6 non-null float64

# dtypes: float64(2)

# memory usage: 144.0 bytes

# Note that some of these data sets are not

This works pretty well for converting R data frames into pandas data frames. Some data structures are a little trickier to convert, like R "time series"

>>> df_AP = pandas2ri.ri2py(r['AirPassengers'])

>>> df_AP

# array([ 112., 118., 132., 129., 121., 135., 148., 148., 136.,

# 119., 104., 118., 115., 126., 141., 135., 125., 149.,

# 170., 170., 158., 133., 114., 140., 145., 150., 178.,

# 163., 172., 178., 199., 199., 184., 162., 146., 166.,

# 171., 180., 193., 181., 183., 218., 230., 242., 209.,

# 191., 172., 194., 196., 196., 236., 235., 229., 243.,

# 264., 272., 237., 211., 180., 201., 204., 188., 235.,

# 227., 234., 264., 302., 293., 259., 229., 203., 229.,

# 242., 233., 267., 269., 270., 315., 364., 347., 312.,

# 274., 237., 278., 284., 277., 317., 313., 318., 374.,

# 413., 405., 355., 306., 271., 306., 315., 301., 356.,

# 348., 355., 422., 465., 467., 404., 347., 305., 336.,

# 340., 318., 362., 348., 363., 435., 491., 505., 404.,

# 359., 310., 337., 360., 342., 406., 396., 420., 472.,

# 548., 559., 463., 407., 362., 405., 417., 391., 419.,

# 461., 472., 535., 622., 606., 508., 461., 390., 432.])

Note: in R our "time series" object appears to have column names (months) and row names (years). These fields are not readily available to use as attributes in either R or python. In R the row names are internally represented by time series attributes with start=1949, end=1960, frequency=12.

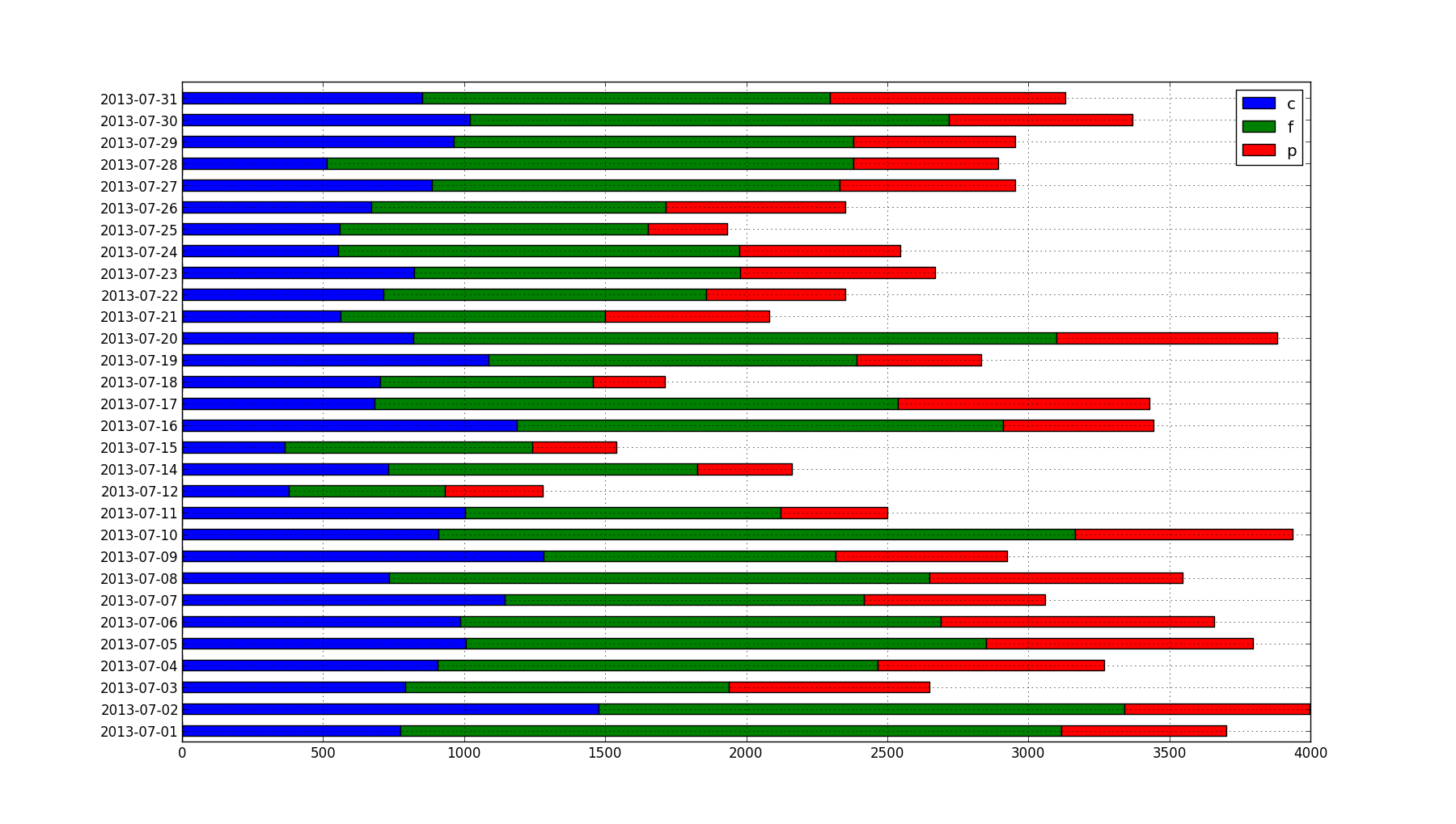

This breaks down my caloric consumption for each day by carbohydrates (blue), fat (green), and protein (red). I have data from March 2013 through August 2013, but I chose to drill down on just July. In this month, I'd been experimenting with high-fat, low-carbohydrate/ketogenic diets for about 12 months and meticulously logging my food consumption, among other things. By July, the experiment was over and I'd begun to consciously increase my carbohydrate intake, so it should look a little more "balanced" than prior low-carb months.

This breaks down my caloric consumption for each day by carbohydrates (blue), fat (green), and protein (red). I have data from March 2013 through August 2013, but I chose to drill down on just July. In this month, I'd been experimenting with high-fat, low-carbohydrate/ketogenic diets for about 12 months and meticulously logging my food consumption, among other things. By July, the experiment was over and I'd begun to consciously increase my carbohydrate intake, so it should look a little more "balanced" than prior low-carb months.